John Muir. Edward Abbey. Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt. Ansel Adams. Aldo Leopold. These heroes of public lands have many things in common, including being old, white men. While the history of America’s Public Lands seem to be only filled with members of the patriarchy, there are hundreds, if not thousands of others who deserve the same credit and attention. One of those is Herma Albertson Baggley, who lived from 1896-1981. The other is Marguerite Lindsley, who lived from 1901-1952.

Unless you scour the internet for Herma Albertson Baggley, you probably have no idea who she is. Yet, she is one of the most important women in the history of the National Park Service. Born in Iowa, Herma Albertson left home in the fall of 1921, traveling west to attend the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho. For the next few years, she studied diligently at the idllic town, surrounded by both the rolling beauty of the Palouse and the forests, rivers and mountains on the Idaho Panhandle. Majoring in botany, with a minor in philosophy, Herma was apparently like most freshly graduate college students, looking to dive into work somewhere that would fulfill her major. She “settled” on working at summer at Yellowstone National Park as a naturalist.

While she paid her room and board as a pillow puncher at the Old Faithful Lodge, she was quite active in encouraging others to go out and explore Yellowstone, helping to create the first nature trail around the Old Faithful geyser area. She guided visitors around the region, served as a substitute lecturer at the Old Faithful Lodge and even kept displays of the wildflowers found around Yellowstone in the famous lodge. Attendance for the events she led skyrocketed, helping Yellowstone officials to make the decision to hire her full time.

For the next three years summers, Herma was an amazing guide in the park, educating and entertaining guests form all over the world, using her megaphone to deliver interpretive talks during hikes around the Old Faithful region. After an injury, she was transferred up to Mammoth Hot Springs, where she worked in the Mammoth Museum and Information Office. It was during this time that things really started happening for Herma.

Since Yellowstone was closed due to wintery, snowy conditions, Herma spent the fall, winter and spring months teaching high school science, garnering the attention of her alma mater, the University of Idaho. U of I offered her a graduate fellowship in the botany department, receiving her master’s degree in the subject in 1929. For a year, she was an instructor at the university, before she stepped away to become an Assistant Park Naturalist. Within a year, she was promoted and became the very first woman in Yellowstone to be appointed Junior Park Naturalist.

For the next seven years, Herma’s work would become the standard for National Park Naturalists. She wrote 22 articles for NPS publications, including the famous Yellowstone Nature Notes. At 42 years of age, she wasn’t even close to being done. In 1936, Herma co-authored the book “Plants of Yellowstone National Park,” which, due to its incredible depth and detail, is still used in the park today. She also fought to improve living conditions in our National Parks for both employees and their families. The argument she used was simple- if you improve housing and other benefits, you would be able to recruit better-qualified staff. Thankfully, her voice was listened to and today, NPS employees have much better housing and benefits, bringing in talents, passionate and professional staff that we all know and love.

The story of amazing women in Yellowstone didn’t start with Herma.

The very first permanent female park ranger, Maguerite Lindsley, was also in Yellowstone and also has quite an amazing story. Maguerite’s father was Chester Lindsley, the Park Superintendent when the park transitioned from being controlled by the US Army to the Department of Interior. Born in 1901, she lived in the park and was raised in Yellowstone, giving her a firsthand look at the park throughout the year. Deeply connected to the land, she stayed close to home for college, getting an undergraduate degree from nearby Montana State University. She then moved to Pennsylvania and attended the University of Pennsylvania, receiving a master’s degree in bacteriology. During the summers, the pull of Yellowstone stayed with her, calling her back to work as a temporary ranger-naturalist in the park.

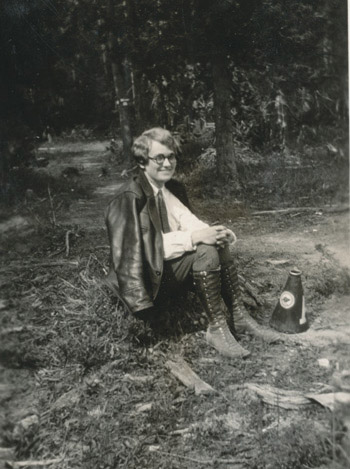

After college, Maguerite was somewhat of a badass. In 1924, she quit the job she had just gotten on the east coast, bought a motorcycle and traveled across the county, heading back to Yellowstone. Within one year, her skills and knowledge couldn’t be denied and in 1925 was named the first female park ranger in the United States.

According to the National Park Service: “Marguerite Lindsley’s position as park ranger earned her some interesting nicknames like, “Geyser Peg” and “Paint Pot Peg.” On a three-week horseback park tour, she was leading a group of visitors through a thermal area when she fell through the crust into boiling mud. Although she suffered burns on her leg up to her knee, she still took the opportunity to teach the visitors about the dangers of thermal features. In 1928, Marguerite Lindsley married another Ranger and returned to seasonal Ranger employment. Although she no longer worked as a Ranger during the winter, she and her husband lived in the park all year round and she routinely joined her husband on ski patrols and back country trips.”

While Maguerite Lindsley’s career was brief, she impacted the right of women to be a part of the great outdoors and be in leadership positions around National Parks. Facing sexism and a myriad of other problems, Maguerite ignored the naysayers and kept working hard, helping to provide the blueprint for millions of other women to succeed in Public Land careers.

This post was written in one hour for my #NatureWritingChallenge, where this week’s topic was “Who is an unsung figure of importance for Public Lands that deserves more attention?”

Want to join in on the fun? Read more about this challenge here.